A Primer on Network Effects

As the crypto industry matures, success is (thankfully) shifting away from creating hype and speculation (“token is the product”) and toward fundamental value of the underlying business. I have seen the terms “network effects” or “moat” (which network effects are a key driver of) thrown around on my timeline in increasing frequency. These are used to describe and identify businesses with strong defensibility that can sustainably generate revenue.

Yet, the discourse remains superficial, failing to derive actual insights into a) what creates network effects, b) how to analyze networks, c) how network effects can be monetized and to what degree.

This article aims to establish a shared understanding of network effects as the basis for productive discussions going forward.

Defining Network Effects

A network effect is a powerful phenomenon where the value of a product or service increases for both new and existing users as more people use it. It is, fundamentally, a demand-side economy of scale.

In plain terms, the product gets better because more people are using it, creating a positive feedback loop that drives growth and retention.

Of course, it’s not that easy and we’re getting into the details now.

Taxonomy of Network Effects

Direct (Same-Side) Network Effects: The simplest form. An increase in usage leads to a direct increase in value for other users of the same type. E.g. Email or messenger

Indirect (Cross-Side) Network Effects: Common in multi-sided platforms. Growth on one side (e.g. sellers) increases the value for the other side (e.g. buyers)

Ecosystem Effects: A specific form of indirect network effect that captures the value added by complementary products and services (e.g. third-party apps on a platform)

Data Network Effects: Even if users do not directly benefit from interacting with other users, the product’s core value can improve through learning from aggregated user data.

Laws of Network Effects

The laws of network effects describe how much network value increases with each new user - how network value scales.

There are different laws depending on the type of network interactions. The two most prominent ones for digital networks are Metcalfe’s and Reed’s Law.

Metcalfe’s Law: States that the value of a network is proportional to the number of users squared (V ∝ N2). This applies best to networks where every user can theoretically connect with every other user (e.g.email).

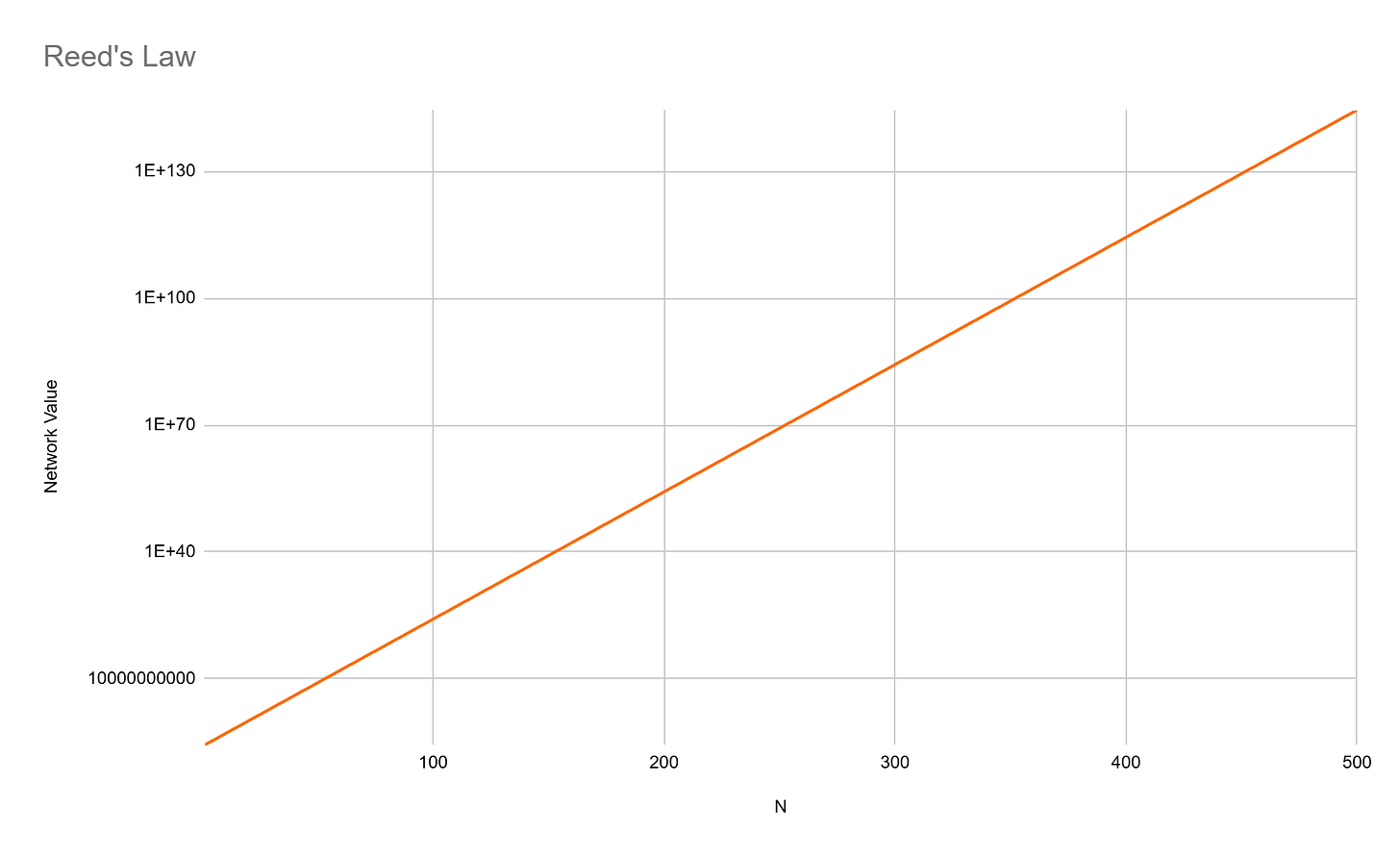

Reed’s Law: Argues that value scales exponentially (V ∝ 2N). This is for networks where users can easily form groups and subgroups (e.g., Discord servers, Reddit communities).

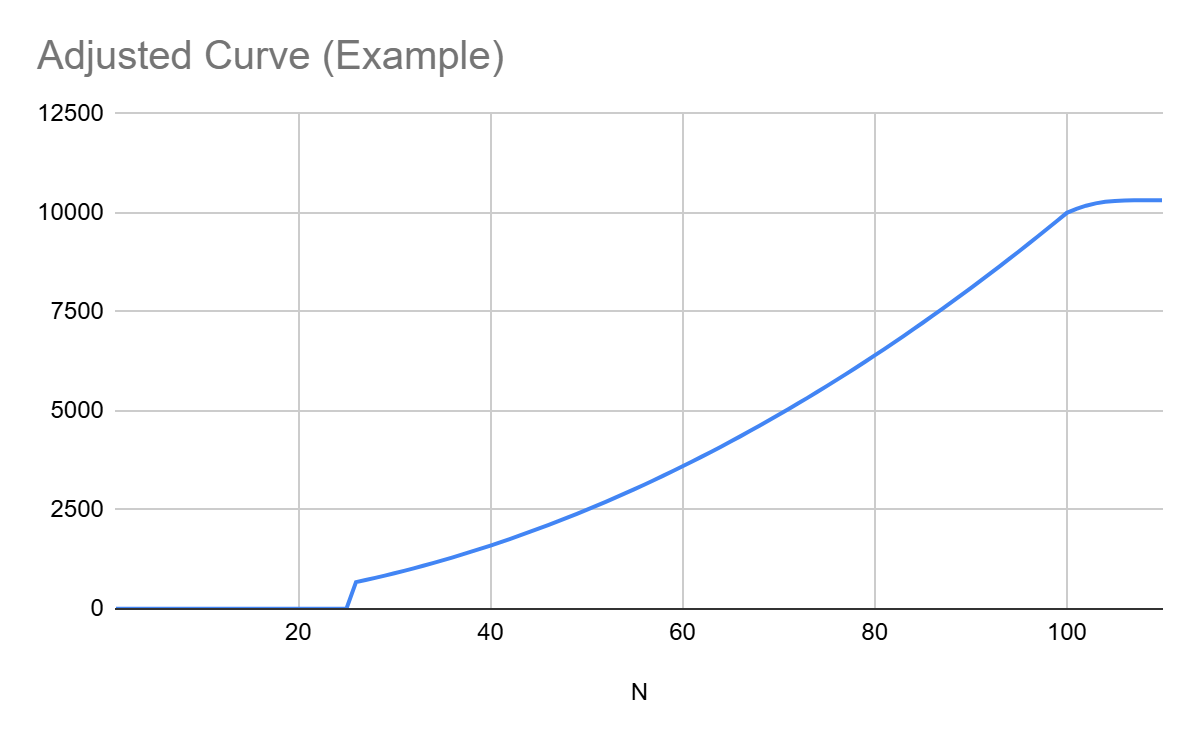

It’s important to understand that these are rough frameworks that are supposed to act as a frame of reference. They are too simple to estimate the actual curves of network value. I recommend to first identify which law generally applies to get an initial curve for the network value and afterwards adjust the curve based on deeper analysis, including:

Asymptote of Value: The classic laws suggest infinite growth, but in reality, the value added by a marginal user decreases over time (e.g. the 1000th Uber driver vs the 10th). Also, networks often have a natural ceiling at which value stalls, either technical or human. For example, a social network user can only maintain a finite number of close relationships (often cited near Dunbar’s Number). Or for blockchains, block space is limited

Critical Mass: Below this essential threshold, the network value is near zero. Users take the risk that the value never materializes, making incentive mechanisms (like early token rewards) crucial for bootstrapping.

The Quality of Users: The laws only consider the number of users (N), not the quality of each user added. The value a user brings in terms of engagement, transaction volume, or adding unique supply is essential. Other laws such Beckstrom’s attempt to address this, defining network value as the net present value of the transactions facilitated by the network, minus the transaction costs. This shifts the focus from the number of nodes in a network to the realized economic activity.

Social network analysis comes in handy here to identify high-value users. More on this later.

Networks need to optimize for activity between users, not just number of users. That means acquiring and retaining high-value users and creating the right conditions for them to transact (e.g. discovery/matching, balance of sides in multi-sided networks). Usually, networks need to bootstrap the supply side. If the network has PMF, demand will follow

The maximum theoretical scale a network can reach depends on its ability to expand into adjacent markets or categories. Multi-purpose networks have a wider array of potential use cases and therefore a higher TAM of users. The risk is that interaction times between users slow down as new user groups are onboarded which makes it harder to find relevant counterparties and thereby decreases network value.

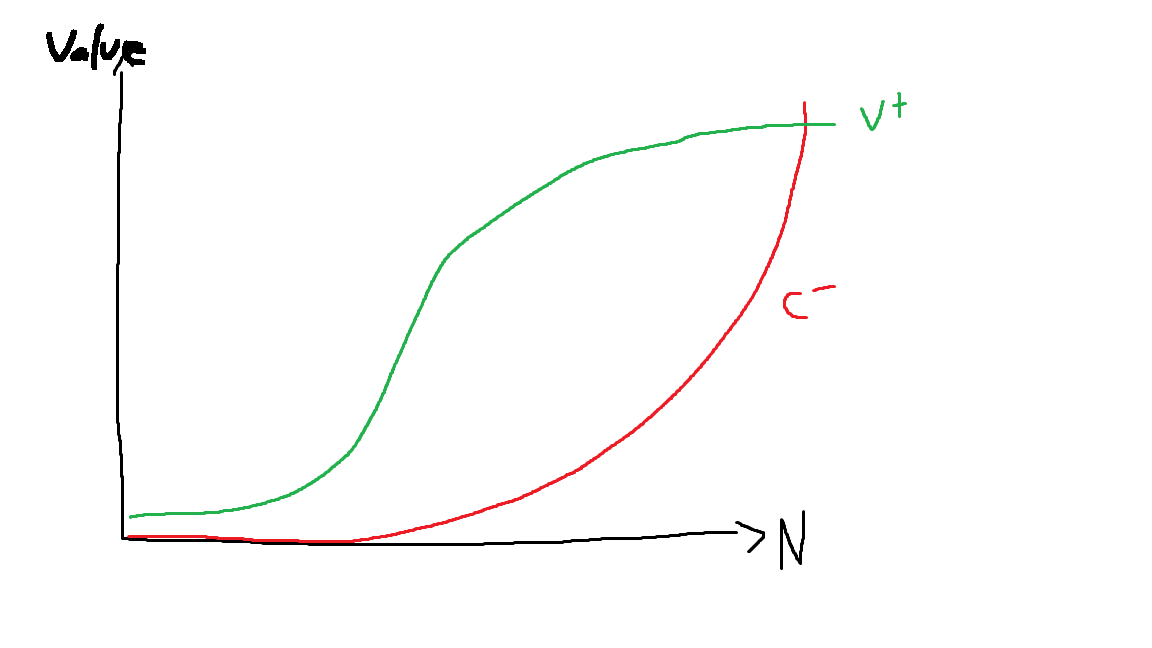

Positive vs Negative Network Effects

Network effects are not purely positive. As a network grows, costs and frictions emerge, potentially creating an upper limit on the net value.

Positive Effects (V+): Include liquidity (faster matching), utility density (higher likelihood of finding what you need), and standardization (easier collaboration). These effects follow the Metcalfe/Reed curves, accelerating after critical mass and eventually plateauing (asymptote of value).

Negative Effects (C-): Include congestion (slowdown of service, high latency, high gas fees on a blockchain) and pollution/noise (too much content or spam, making it harder to find what you’re looking for). These costs can remain low early on but accelerate rapidly at scale, especially where technical capacity limits are hit.

The network’s Net Value is described by

Since V+ eventually flattens while C- can continue to rise exponentially (e.g., due to capacity limits), the Net Value eventually declines, forming an Inverted U-Curve. This peak is the point of optimal network size.

Determinants of Network Strength

Strong network effects create defensibility (a moat). Strengths is determined by the following factors

Switching Costs

The pain, financial, time, or psychological, of leaving the network. The higher the switching costs, the stronger the moat. Examples for switching costs include data loss, the social graph/reputation (losing reviews or connections), the need to learn a new workflow, or an exit fee.

Prevention of Multi-Tenancy

If users can easily use competing networks simultaneously (e.g., multiple trading platforms), the network effect is weak. Platforms fight this by offering unique, non-interchangeable supply (e.g., specific properties on Airbnb vs. standardized Uber drivers).

Minimizing Disintermediation

Disintermediation describes the risk that users transact off-platform so the network owner cannot monetize the network effects. Commoditized marketplaces (e.g. Uber: don’t need the same driver) exhibit a lower disintermediation risk. There’s generally reduced risk if users are engaging with different counterparties every time, and the value of the interaction is high, therefore trust in payment settlement, potential insurance through the network etc are valuable.

Cluster Structure (Local vs. Global)

Global networks are highly defensible because the network effect is shared by everyone. Local networks (value added only to nearby users, e.g., location-based dating apps) are weaker, as a competitor can win one region at a time and network value scales slower. For local clusters, nodes that bridge clusters are key.

Network Liquidity

The ability for users to quickly find each other and transact. High liquidity fosters economic activity which creates actual network value that can be monetized. It is maximized when transaction frequency is high and, in multi-sided networks, when the user sides are optimally balanced (e.g. enough seller capacity to meet buyer demand). Liquidity is further supported by:

Networks that work asynchronously (users do not have to be active at the same time) can scale more easily. The need for synchronous activity is better manageable if the user behavior is planned (users are active and online at the same time)

Side switching: in multi-side networks, users may be able to take on multiple roles. This helps liquidity and reduces the effort required to reach critical mass

Dependency Risk

High-value nodes (e.g. celebrity influencers, top app developers) capturing too much of the network’s connections/value creates a risk of supply-side concentration, making the network highly dependent on a few key nodes. This a) leaves the network vulnerable to tries by competitors to vampire attack these high-value nodes and b) gives (pricing) power to nodes.

Measuring Network Structure

Social Network Analysis (SNA) assesses how nodes are connected with each other to measure the strengths and vulnerabilities in the network’s topology. For instance, SNA can measure how well-distributed a network is, which creates strength (not dependent on a number of handful high-value nodes). Furthermore, SNA can be used to assess the value an individual user brings to the network.

Node-Level Measures (Identifying Key Players)

Degree Centrality: The number of direct connections a user has. Identifies “hubs” (influencers).

Betweenness Centrality: Measures how often a node acts as a “bridge” between two separate groups. These users are critical for connecting disparate clusters.

Eigenvector Centrality: Measures influence based on the quality of a user’s connections (connecting to high-scoring nodes gives you a higher score).

Network-Level Measures (Identifying Cohesion)

Clustering Coefficient: The likelihood that a user’s connections are also connected to each other. A high coefficient means the network is tightly knit, increasing defensibility (it’s much harder to leave a dense group).

Density: The ratio of actual connections to all possible connections. While high density can lead to faster information flow (efficiency), too much density risks information redundancy and noise (C-)

Average Path Length (APL): The average number of steps required to get from any one user to another. A low APL (a “small-world network”) indicates efficient value diffusion.

All these measures can be upgraded by adding activity data e.g. how often does a connection between two nodes actually get used.

Monetizing Network Effects

The ability to monetize is directly tied to the strength of the network effect (i.e., the pricing power of the moat). Strong network effects allow for higher take rates and more friction-inducing monetization models.

Monetization tools include:

Interaction Fees (Take Rates): Charging a fee per transaction facilitated (e.g., commissions).

Premium Tiers: Offering advanced features or enhanced network access (higher quality/quantity of interaction) to power users (e.g., SaaS models).

Paywall: Restrict network access to paying users

Complementary Products built on top of the network

Derived Products: Monetizing the aggregate data generated by the network (e.g., analytics).

Advertising: Monetizing attention (often by leveraging data network effects).

The key strategic decision is choosing a model that does not destroy the network effect it is trying to monetize. For instance, limiting interactions in social networks via a hard paywall often kills the virality and utility that built the network in the first place.

Fantastic breakdown! The inverted U-curve insight really reframes how to think about network growth - that negative effects can actualy outpace positive ones at scale. I've seen this firsthand where adding more users made discovery harder rather than better. The V+ minus C- formula gives a concrete way to spot when size becomes a liablity.